With so many new AI tools out these days, there’s got to be some good ways to transcribe, classify and make synopses of large collections of notes and recordings.

One transcription service is https://www.mygoodtape.com/pricing

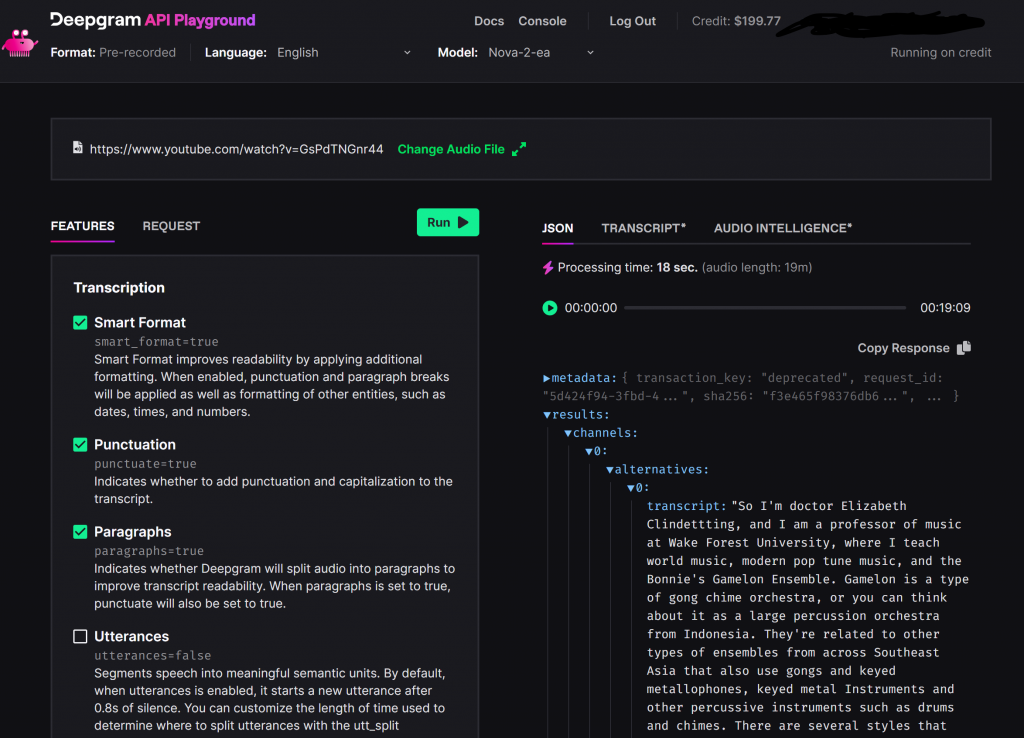

Another is Deepgram @DeepgramAI that has an AI speech-to-text API.

One gets a $200 in credit (up to 45K mins) of free transcription and understanding at http://dpgr.am/462be55 (2 short transcriptions cost me $0.33)

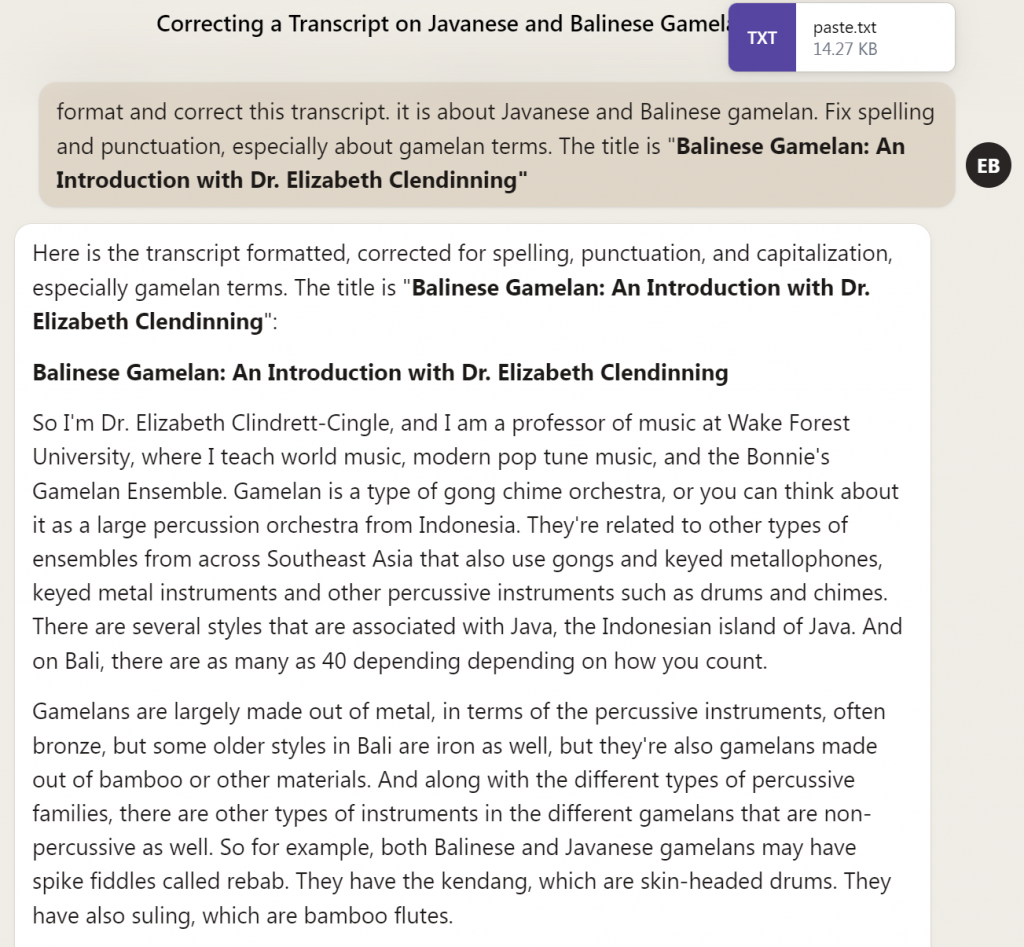

Then use that output with LLMs like Claude 2 to fix and change:

One can also explain the jargon to one’s LLM and make it more accurate.

Here is the unedited text resulting from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GsPdTNGnr44 using https://playground.deepgram.com and https://claude.ai :

“

**Balinese Gamelan: An Introduction with Dr. Elizabeth Clendinning**

So I’m Dr. Elizabeth Clindrett-Cingle, and I am a professor of music at Wake Forest University, where I teach world music, modern pop tune music, and the Bonnie’s Gamelan Ensemble. Gamelan is a type of gong chime orchestra, or you can think about it as a large percussion orchestra from Indonesia. They’re related to other types of ensembles from across Southeast Asia that also use gongs and keyed metallophones, keyed metal instruments and other percussive instruments such as drums and chimes. There are several styles that are associated with Java, the Indonesian island of Java. And on Bali, there are as many as 40 depending depending on how you count.

Gamelans are largely made out of metal, in terms of the percussive instruments, often bronze, but some older styles in Bali are iron as well, but they’re also gamelans made out of bamboo or other materials. And along with the different types of percussive families, there are other types of instruments in the different gamelans that are non-percussive as well. So for example, both Balinese and Javanese gamelans may have spike fiddles called rebab. They have the kendang, which are skin-headed drums. They have also suling, which are bamboo flutes.

I can’t play this. Thinking about Javanese and Balinese gamelans, to an untrained eye, they look kind of similar. They both have large gongs. They both have smaller horizontal gongs, they both have ket instruments, and in some ways, they are similar in terms of having usually a cyclical foundation is cyclical form based on the gong cycle, and then having a core melody and various types of elaboration. And as well, many of these ensembles are controlled in terms of tempo or dynamics by the kendang.

However, there are also plenty of differences. So, for example, the Javanese Gamelan has a number of gongs, both the great gong as well as gongs according to every pitch of the gamelan. The Balinese Gamelans tend to only have 1 or 2 large hanging gongs and 1 smaller one, so there’s much less presence in terms of distinctive pitches. So that’s one difference. Another is in terms of types of melodic elaboration.

So both have a core melody in Central Javanese Gamelan gendhing or a pokok in Balinese gamelan that has other instruments that elaborate upon it, and there are different ways of doing that. These 2 are the jagogan. They anchor the core melody. While the jagogan may have the lower part of the core melody, the cengceng, the smallest keyed instruments, take up the high end. You may have seen these if you tuned in to my senior recital.

Most of the elaboration is carried out by the instruments known as gangsa. And there are 2 types of gangsa, 1 lower and 1 higher. These are the lower and thus larger instruments, the gangsa pamade. In this particular set, there are 4 each of the pamade and the kantilan. So this is exactly like the gangsa pamade, but this being the kantilan is about an octave higher.

The main playing technique you’ll find on instruments such as these is the muting or the dampening that occurs after hit a note. So for instance, if I play 1, 2, 3, I don’t do anything with my left hand. I’m right handed, so I play with my right. And I dampen with my left. When I hit the 2nd note, may hit 2.

The instant that I hit the 2nd note, unmuting or dampening with the other hand. This is one of the big learning curves for people who are getting used to an instrument like this. But when you get really good at it, you can just fly up and down this little keyboard. Keeping time throughout all this it’s an instrument called the kajar, which comes from the root word to teach. But my personal favorite instrument to play in this whole ensemble is the reyong.

Adding shimmer and color to whatever melodic and rhythmic collaborations that reyong is doing is the cengceng, which is onomatopoetic because, well, just listen to it. It’s very loud. Of the interesting features about Balinese gamelan elaboration styles is that, the way in which one of the ways in which you elaborate the core melody is through multiple parts that interlock. And, in that case, you also have a 2 part division generally between polos and sangsih, as they’re called. One which is thought of this being more straight or more regular and one that is more following.

They’re although they’re often glossed as being more on and off the beat. The types of interlocking that are created by polos and sangsih are, quite variable. There are a number of different styles that you can pursue this is one of the interesting facets of the texture and it’s something that enables gamelan musicians to play very, very fast because they are dividing the parts rather than attempting to play a single elaboration, each person themselves. This also ties back, of course, into the cultural idea of, dividing labour and assigning labor so that you have 2 individuals working together to create a part rather than having 1 person do it themselves. And it creates both a difference in the feeling of the music, the actual sound, but also the feeling of how the ensemble’s working to have 2 people working together to create elaboration.

There are certain elements also within the way that form works as well. So while each of these styles generally revolve around gong cycle and core melody. In central Javanese Gamelan, for example, the way the sort of time rhythmic structure is called irama, and you can have, formal switches and sections that are types of formal sections that make up the form. Usually, the strong beat is the first beat, but with a gong cycle, the the great gong in lot of Balinese music comes in at the end. Yes, absolutely.

So the idea is basically that phrases are leading towards the gong. Of course, since if it’s a cycle then that’s you could debate that point, but, the idea being that the feeling is that everything is moving towards the gong. And that is generally true of both Balinese and Javanese gamelan. Moment of that the micro timing of that is somewhat different, to a, you know, an ear trained on a metronome. In particular, Javanese gongs and the arrival of the gong tends to happen a little bit late metrically.

And in Bali, they tend to have it happen more directly on metronome time. There are 3 gongs here. The largest this is the great gong or the gong ageng. It’s got the best sound. It’s also got the name of the ensemble.

So when you name an ensemble, when you christen 1 in a ceremony, you actually name the gong. The middle sized gong here is kempur. And the smaller gong down here is either called suwukan or kempul in the style. So that was the back of the stick. So altogether, if you were to have an 8 beat cycle, it might sound something like this.

8. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. 8. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. Although gong cycles can last for up to 64 beats, so you gotta really count if you’re playing the gongs.

Balinese gamelan has paired tuning, which is actually fairly distinctive. The Javanese does not in the same way. And that means that instruments are conceived of as having a pair or a mate, so there are 2 instruments that may look the same but are thought of as being a pair. And the way that they are tuned is that, 1 set of or 1 half of this pair is conceived of as being female, wadon, and it has a slightly lower pitch. And the upper pitched one, lanang, is male. And when the 2 of these instruments, this pair plays together, you get a sort of shimmering sound called ombak, which means waves. And this is a distinctive feature of the sound, and without it, the gamelan sound is actually considered to be dead.

So don’t ever get a piano tuner trying to, you know, equal temperamentize the gamelan because that would actually destroy what’s, beautiful and what’s sort of its characteristic. The female pitches, the wadon being lower, is associated with the earth, whereas the male, being higher is associated with the heavens. But the important part really is that just like in Balinese society where most of the roles of traditional society, the tasks are divided between men and women, each with a role to play. You can’t have a gamelan with only male or only female instruments. That the sound actually requires both to be complete.

And does this tie into the idea that the instruments have souls and that they are respected as having souls? So, I don’t know of a direct tie in to the idea of instruments having souls, but it’s definitely true that the instruments are believed to be possessing of spirits, and that’s, if you see people interacting with gamelan instruments, that’s one of the reasons that will explain some of the behavior that you’d see as far as, people not stepping over the instruments. That’s considered to be a sign of respect. The fact that the drums, for example, in Balinese gamelan in particular, generally have badhut and dangdut. They have clothing, like a human would have clothing.

And the instruments in Balinese gamelan, in particular, are also generally really carved and painted. And so those are aspects sort of of their external being or their external clothing as it were.

So let’s get into the tuning of the gamelan here. So this is a fusion between the angklung and the gong kebyar styles. Yes. So and having played with this group for some time, I still am not entirely sure what part is the angklung and which part is the gong kebyar. Absolutely. Yeah. So there are two overarching terms to describe tuning systems for gamelan, slendro and pelog. And in Javanese gamelan, this is actually interesting.

So a complete set of Javanese gamelan has different instruments that are tuned to each tuning. So you’ll often you’ll see them placed at, a right angle to each other, and the instrumentalists will play sit towards 1 instrument to play slendro, and then if they switch to a part of a piece or a piece that’s in pelog, they will literally move their body to the other instrument garapan. Balinese gamelans tend to be 1 or the other, traditionally. And so what what are these tuning systems like.

So slendro is a 5 pitch tuning system. It’s a pentatonic system. Whereas pelog has 7 pitches. And each of these have different names and it depends on which configuration of instrument or, configuration of pitches are on each instrument as to how the individual keys, you know, you point to them and have them be named. So gamelan gong kebyar, which is a type of gamelan that arrived arose in Bali in the early 20th century, whose name really means to, like, flare up or flash up like a spark. This is a sort of newer gamelan and that’s only just over a 100 years and its system is a scale of which there are 7 pitches. It uses a tuning called selisir, which only is 5. So, the tones ding dong ding dong and dong, which if you were in the west, you might number for convenience 1, 2, 3, 5, 6. So it’s leaving out pitches 4 and 7 of 7.

Now angklung is a 4 or 5 pitch, type of gamelan. It actually only has 4 or 5 actual keys on a keyed instrument. Gong kebyars are much larger. Angklung has 4 or 5 actual keys on a keyed instrument. And, traditionally, they the tuning for angklung was its own thing. Would be called as opposed to the type of tuning for called.

But over time, cengkok madenda has it seems that it has moved more closely to a more standard devised slendro of 5 pitches. So ours is an interesting gamelan because, it is a hybrid. I believe it’s the only hybrid of its type in North America. It is basically what’s called a gamelan kamang kirang, which is a 5 tone slendro in its tuning profile. But instead of only having 5 keys on the gangsa instruments. We actually have an extended range. So that the idea being that you can play angklung repertoire in the middle of the set and just ignore the keys that wouldn’t be included in a traditional angklung instrument. But then you can also play gong kebyar repertoire, that maps physically directly to lean on to the instruments. Although you are playing it in slendro instead of pelog, which is a little bit confusing for experienced musicians from time to to sort of make that aural switch.

I had first played Balinese gamelan at, in middle school band camp at Florida State when I was about 12 years old. And I they got you young. What? They got me young. Yeah. But the thing is I didn’t even remember this until a few years go. Because, that was sort of an afternoon elective and you could do I think another time I did, music theory class or I know I did steel band one time. So they had these enrichment electives for band and orchestra joined choral kids, to do as part of summer camp. I completely forgot about it, basically, until I went to college and got interested in did an ethnomusicology, and I only began to play as a grad student when I came back to Florida State. And, it stuck with me not from the initial time that I played with it oddly because there are so many different and fabulous those types of ensembles to join there. But it was the combination of starting to also study dance that I began to really think more critically about the music to understand its structure better.

And then also the dancer that I was working with just happened to think to bring her dance costumes and happened to get connected with this ensemble and was doing it basically, you know, to make some extra money or and or as a hobby. I’d also been pursuing in in a degree in ethnomusicology, I’ve been reading a number of our required readings and realized that gamelan had basically traveled alongside the development of that scholarly discipline since its beginnings in the United States, since its modern existence as a discipline. And I found that to be absolutely fascinating. Why were these instruments here? Where did they come from? What relationship did gamelans, like the one I was playing in, have to gamelans in Indonesia? And so ultimately that led me to start traveling to Indonesia. And end up writing a book that’s still in progress about the history of American gamelan. Yes. Yeah.

So I have, a book that I hope will be, on our shelves that’s about Balinese gamelan and higher education, and it follows closely the, life and the work of 1 family, the Tenzer family, with whom I have worked now for almost an entire decade and who’s worked with a number of my students as well, as they developed, a set of academic and community gamelans in the front rage of the Rocky Mountains, but it draws on other perspectives from a number of Americans and Balinese people who are teachers and musicians and scholars who are bringing gamelan to a transnational audience.

“

It seems that using just those two tools can get one above 90% of the way towards something publishable.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *